How caching works

How caching works

What is caching?

Caching involves the storage of file duplicates in a temporary location known as a cache, with the aim of facilitating quicker access. While a cache can technically refer to any temporary storage location for files or data, the term is commonly associated with Internet technologies. Web browsers utilize caching to store HTML files, JavaScript, and images, enabling faster website loading. Similarly, DNS servers cache DNS records to expedite lookups, and CDN servers cache content to minimize latency.

To grasp the functioning of caches, one can draw parallels with real-world caches containing food and other provisions. For instance, during explorer Roald Amundsen’s 1912 return journey from the South Pole, he and his team relied on the caches of food they had strategically stored along the way. This approach proved far more efficient than relying on supplies delivered from their base camp as they progressed. Likewise, Internet caches serve a comparable purpose by temporarily storing the “supplies” or content required for users to navigate the web. What does a browser cache do? Whenever a user visits a webpage, their browser retrieves a significant amount of data to render the webpage. To enhance the speed at which pages load, browsers store a majority of the webpage’s content in a cache on the device’s hard drive. This caching process involves saving a duplicate copy of the webpage’s content locally, so the next time the user accesses the page, a significant portion of the content is already available, resulting in faster load times.

These cached files remain stored until their time to live (TTL) expires or until the hard drive cache reaches its capacity. The TTL serves as a duration indicating how long the content should be cached. If desired, users also have the option to clear their browser cache.

What does clearing a browser cache accomplish?

When the browser cache is cleared, each webpage that loads will appear as if the user is visiting it for the first time. Clearing the cache ensures that any incorrectly loaded content from previous visits is refreshed and can be displayed correctly. However, it’s important to note that clearing the browser cache may temporarily slow down page load times.

What is CDN caching?

A content delivery network, known as CDN, operates by storing content, such as images, videos, or webpages, in proxy servers positioned closer to end users than the original servers. Proxy servers receive client requests and forward them to other servers. By bringing the servers closer to the requesting user, a CDN facilitates speedy content delivery.

Visualize a CDN as a network of grocery stores: Instead of traveling all the way to distant farms where food is cultivated, which could span hundreds of miles, shoppers visit their local grocery store, requiring less travel time. Grocery stores stock food sourced from remote farms, resulting in minutes rather than days spent on grocery shopping. Similarly, CDN caches “stock” Internet content, leading to significantly faster webpage loading times.

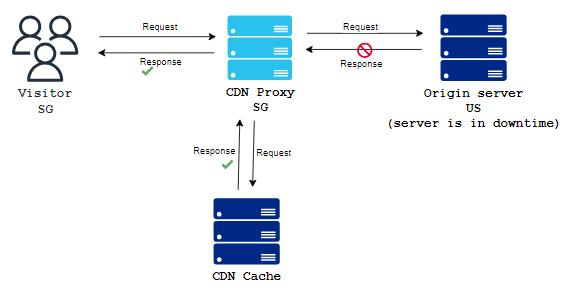

When a user seeks content from a website employing a CDN, the CDN retrieves that content from an origin server and retains a copy of it for future requests. Cached content remains within the CDN cache as long as users continue to demand it.

What is a CDN cache hit? What is a cache miss?

A cache hit happens when a client device sends a request for content to the cache, and the cache already has that content stored. On the other hand, a cache miss takes place when the cache does not have the requested content.

When a cache hit occurs, the content can be loaded much faster because the content delivery network (CDN) can promptly deliver it to the end user. In the event of a cache miss, the CDN server forwards the request to the origin server and caches the content once the origin server responds. This way, future requests will result in a cache hit.

Where are CDN caching servers located?

CDN caching servers are strategically positioned in data centers worldwide. Toffs, for example, maintains a vast network of CDN servers in 300 cities across the globe. This extensive distribution allows them to bring the servers as close as possible to end users, ensuring efficient access to the content. In essence, a data center housing CDN servers is commonly referred to as a location within the CDN network.

How long does cached data remain in a CDN server?

When CDN servers receive a response from websites containing the requested content, they also receive the content’s TTL (Time to Live), which informs the servers about the duration for which the content should be stored. This TTL information is included in a section of the response known as the HTTP header. It specifies the caching duration in seconds, minutes, or hours. Once the TTL expires, the cache automatically removes the content. Additionally, certain CDNs may proactively purge files from the cache if the content remains unused for an extended period or if a CDN customer manually requests the removal of specific content. How do other kinds of caching work? DNS caching occurs within DNS servers, where they retain recently performed DNS lookups in their cache. This caching mechanism enables the servers to swiftly respond with the IP address of a domain without having to query nameservers.

In the case of search engines, they employ webpage caching to store frequently appearing webpages from search results. This caching allows them to address user queries, even if the corresponding website is momentarily inaccessible or incapable of responding.

How does Toffs use caching?

Toffs provides a globally distributed CDN (Content Delivery Network) consisting of 300 PoPs (Points of Presence) across the world. Users can benefit from Toffs’s free CDN caching services, while those who opt for the paid CDN have the added advantage of customizing their content caching preferences. Toffs’s network operates on the Anycast principle, enabling content to be delivered from any of its data centers. This means that regardless of their geographical location, a user in London and another in Sydney can access the same content seamlessly, as it is loaded from nearby CDN servers located just a few miles away.